An Introduction to the Process of Creating Systematic Reviews

Systematic reviews are an indispensable part of evidence-based practice (EBP): They help clinicians decide on the advisability of a particular course of action, for example, what instrument to utilize to assess the seriousness of a problem, what procedure to use for treating a problem, and what information to give patients/clients when they ask questions about prognosis. The systematic review is not the only part of EBP, and clinicians should not forget that the values and preferences of their patients/clients should play a role in decision making, as well as the clinician’s own expertise and level of training in advanced assessment and treatment techniques. However well designed, implemented, and reported, a systematic review is never the only part of the puzzle.

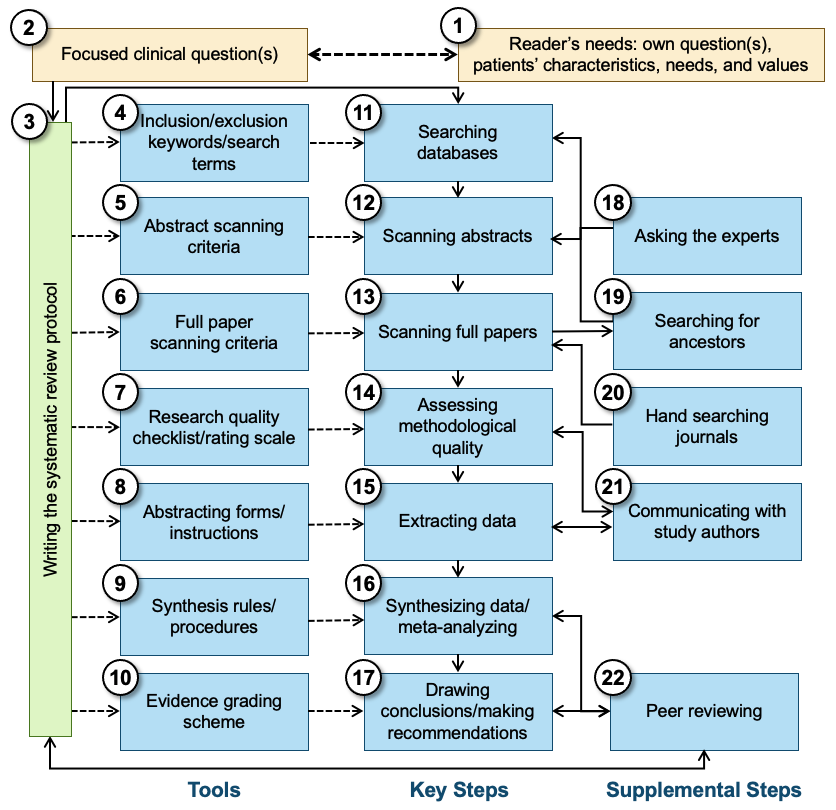

All systematic reviews start with a focused clinical question (See Figure 1, Box 2), and are designed to answer that question using only the findings of relevant, quality-assessed research that has been completed but not necessarily published. It is the responsibility of the clinician or other user of the systematic review to determine whether there is a match between that question and their own question(s) and need for information, including the fit with the patients’/clients’ characteristics, needs, and values (Box 1). A protocol (Box 3) is then written that specifies the research process that will be followed to find the answer to the focused question(s). The protocol typically indicates how the data (the results of existing research) will be identified, evaluated, extracted, synthesized, and used to answer the focused question that started the process, and what criteria will be used to ensure the quality of the synthesis and the dependability of the recommendations, if any. The protocol should specify what methods (Boxes 11–22) and standards or instruments (Boxes 4–10) will be used in all later steps. To minimize bias, the protocol should be developed without knowledge of the findings of primary studies. Ideally, at this stage the authors are still blind to what the review might conclude. Sometimes a group separate from the protocol authors reviews the protocol to make sure that the researchers have indeed proposed feasible and optimal ways of completing all the steps in the review process, at least within the scope of the available resources (Box 22).

Figure 1. Schematic overview of systematic review production and linking the results to the reader’s interests

The protocol specifies which bibliographic and other databases will be used and identifies the inclusion/exclusion criteria as well as key free-text words, controlled vocabulary terms, and thesaurus terms (Box 4) to be used in searching for relevant research (Box 11). Most databases will produce reference information, including an abstract of the paper that was published. However, other databases, such as clinical trial registries, may indicate only that a study was planned, and that follow-up with the investigator or sponsor is necessary to determine whether any findings were published or at least are available. These abstracts are used to screen studies/papers (Box 12), using specific criteria (Box 5) regarding what can be eliminated and what must go on to the next stage: the scanning of complete documents. The best abstract scanning uses two or more individuals who review abstracts independently; their agreement should be reported as an indication of the quality of the screening process.

In the next stage, full papers are scanned (Box 13) to determine whether they indeed are applicable to the clinical question and whether they satisfy the criteria (for age group, treatment type, comorbidities, etc. [Box 6]) set forth in the protocol. Additionally, full texts of published papers are commonly used for ancestor search (Box 19), which is checking the list of references for prior relevant publications that for some reason (a very old paper, a journal that is not indexed, an error by an indexer, etc.) did not make it into the batch of abstracts retrieved from the bibliographic databases consulted. Another method often used to identify research, especially studies that may not have been published or that were published only in reports or other documents often not included in the bibliographic databases, involves contacting experts in a particular area (Box 18). “Hand searches” of the most relevant journals (Box 20) are sometimes used. Systematic reviewers may avoid the latter step, either because of the costs involved or because they trust that other databases (e.g., the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) have been created on the basis of such hand searches. Even with a “small, simple” clinical question, the number of full papers that are thought to be relevant on the basis of a reading of only the abstract can be large, and scanning of the full papers is recommended to determine which papers need to go on to the next step. Again, scanning by multiple readers (Box 13) is used to make sure no paper is accidentally set aside as not relevant.

Many systematic reviews assess the methodological quality of the primary studies they have identified (Box 14), using a quality checklist or even a formal quality rating scale (Box 7). The resulting information may be used to exclude papers or studies altogether, or to weight individual studies in the synthesis phase of the review, and/or in a sensitivity analysis to determine whether research quality makes a difference in the nature of the findings. Because many research reports leave out some information on methods or findings crucial to systematic reviewers, or describe their methods in ambiguous terms, researchers doing a systematic review may want to communicate with the authors of the primary studies to retrieve as much missing information as possible (Box 21). With or without the supplemental information, those completing the quality rating scale or checklist may easily make errors of omission or commission. Therefore, having two or more well-trained individuals (Box 14) do this independently for each paper is recommended.

The next step in the sequence is to extract the data from the papers (studies) that survived the previous stages (Box 15). Using customized forms (or data entry screens linked to a database) and instructions (Box 8), members of the review team identify the information needed in the sources and enter the data in the appropriate fields. Depending on the purpose of the systematic review, this may be bibliographic information (e.g., source journal and year of publication), study characteristics (e.g., number of subjects, use of randomization), and outcomes reported (for instance, specific outcome measures, effect sizes) or aspects of the conclusions drawn by the study’s authors. Also in this stage (Box 15), use of multiple independent extractors is recommended, and the authors of the studies being reviewed may be contacted to get details missing from the published report (Box 21). Steps 13, 14, and 15 can be combined, and they often are combined, in that the same individuals scan in a single step the full papers for eligibility, extract or rate information relevant to the methodological quality of the primary studies, and extract substantive outcome information.

In the data synthesis step, the various primary studies—or at least the elements extracted in Step 15—are combined (Box 16). If the question “Are these studies or findings combinable?” has been answered with “yes,” the common theme (message, finding, etc.) of the primary studies is determined, especially regarding how they answer the clinical questions: “How many studies give answer A, what is the methodological quality of these investigations, and how strong is their support for this (for instance, what are the relevant effect sizes)?; How many give answer B or another answer?” Further analysis in the synthesis phase may address systematic differences between the studies that resulted in answer A versus those that found answer B; authors may also assess whether the trend is different for subgroups of patients/clients, for weaker and stronger studies, etc. In meta-analyses, answering the question of combinability and synthesizing the data are both quantitative.

The existence of explicit synthesis rules and standards that have been defined beforehand (Box 9) is the strong suit of systematic reviews. Decisions regarding how information is combined across studies are guided by the clear rules specified in the protocol rather than someone’s preferences or biases. But the reader should keep in mind that biases may have led to the specification of the rules in the first place, and that sometimes rules are not obeyed. The fact that the protocol mentions rules and standards does not guarantee that the results of the systematic review are dependable. The current document and the AQASR checklist were written to help readers of systematic reviews become critical readers.

While the data synthesis step is akin to statistical analysis in a traditional primary study, the next step—drawing conclusions and making recommendations (Box 17)—is very similar to what is done in primary research. One major difference, however, is that systematic reviewers rely on preset criteria for the strength (quality, quantity, variety) of the evidence when drawing conclusions and making recommendations. These evidence grading schemes (Box 10) may, for instance, state that an intervention can be recommended strongly only if there are at least two large, well-executed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) supporting it. If, however, there are only observational studies, regardless of how many and how well done, the intervention might only be suggested as one out of many options.

Some systematic reviews, especially those sponsored by professional groups or performed with government funds, are different from other types of research in that the protocol calls for a round of external peer review before the findings and recommendations are distributed. This group of experts (which may include methodologists, clinicians, and consumers and which may be the same or different from those who reviewed the protocol before undertaking the study) reviews the draft report, assesses whether the investigators followed their protocol, and determines whether there are, in spite of adherence to a well-written protocol, any major errors (omission of studies, misinterpretation of primary studies, flaws in synthesis, etc.) that resulted in erroneous findings, conclusions, and recommendations. The peer review (Box 22) may be the basis for redoing part of the work, possibly from the step of writing the protocol forward.

Further Reading on the Process of Systematic Reviewing

- Brouwers, M., Kho, M. E., Browman, G. P., Burgers, J. S., Cluzeau, F., Feder, G., Fervers, B., Graham, I. D., Grimshaw, J., Hanna, S.E., Littlejohns, P., Makarski, J., & Zitzelsberger, L. (2010). AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 182(18) E839-E842. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090449

- Brown, P. A., Harniss, M. K., Schomer, K. G., Feinberg, M., Cullen, N. K., & Johnson, K. L. (2012). Conducting systematic evidence reviews: Core concepts and lessons learned. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(8), S177–S184.

- Delgado-Rodríguez, M., & Sillero-Arenas, M. (2018). Systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina Intensiva, 42(7), 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medin.2017.10.003

- Dijkers, M. (2013). Introducing GRADE: A systematic approach to rating evidence in systematic reviews and to guideline development. KT Update, 1(5), 1–9.

- Dijkers, M. P., Bushnik, T., Heinemann, A. W., Heller, T., Libin, A. V., Starks, J., Sherer, M., & Vandergoot, D. (2012). Systematic reviews for informing rehabilitation practice: An introduction. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(5), 912–918.

- Dijkers, M. P., Murphy, S. L., & Krellman, J. (2012). Evidence-based practice for rehabilitation professionals: Concepts and controversies. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(8), S164–S176.

- Engberg, S. (2008). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: Studies of studies. Journal of Wound Ostomy & Continence Nursing, 35(3), 258–265.

- Haber, S. L., Fairman, K. A., & Sclar, D. A. (2015). Principles in the evaluation of systematic reviews. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy, 35(11), 1077–1087.

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (Eds.). (2022). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 6.3. Cochrane. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Hutton, B., Salanti, G., Caldwell, D. M., Chaimani, A., Schmid, C. H., Cameron, C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Straus, S., Thorland, K., Jansen, J. P., Mulrow, C., Catalá-López, F., Gotzsche, P. C., Dickersin, K., Boutron, I., Altman, D. G., & Moher, D. (2015). The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: Checklist and explanations. Annals of Internal Medicine, 162(11), 777–784.

- Institute of Medicine. (2011a). Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13058

- Institute of Medicine. (2011b). Finding what works in health care: Standards for systematic reviews. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13059

- Leucht, S., Kissling, W., & Davis, J. M. (2009). How to read and understand and use systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 119(6), 443–450.

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), W–65.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264-269.

- Muka, T., Glisic, M., Milic, J., Verhoog, S., Bohlius, J., Bramer, W., Chowdhury, R., & Franco, O. H. (2020). A 24-step guide on how to design, conduct, and successfully publish a systematic review and meta-analysis in medical research. European Journal of Epidemiology, 35(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00576-5

- Oxman, A. D. (1994). Systematic reviews: Checklists for review articles. BMJ, 309(6955), 648–651.

- Oxman, A. D., & Guyatt, G. H. (1991). Validation of an index of the quality of review articles. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 44(11), 1271–1278.

- Petticrew, M. (2001). Systematic reviews from astronomy to zoology: Myths and misconceptions. BMJ, 322(7278), 98–101.

- Scheidt, S., Vavken, P., Jacobs, C., Koob, S., Cucchi, D., Kaup, E., Wirtz, D. C., & Wimmer, M. D. (2019). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Systematische reviews und metaanalysen. Zeitschrift fur Orthopadie und Unfallchirurgie, 157(4), 392–399. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0751-3156

- Schlosser, R. W. (2007). Appraising the quality of systematic reviews. Focus, 17, 1–8.

- Schlosser, R. W., Wendt, O., & Sigafoos, J. (2007). Not all systematic reviews are created equal: Considerations for appraisal. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 1(3), 138–150.

- Schlosser, R. W. (2006). The role of systematic reviews in evidence-based practice, research, and development. Focus, 15, 1–4.

- Siddaway, A. P., Wood, A. M., & Hedges, L. V. (2019). How to do a systematic review: A best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 747–770. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

- Treadwell, J. R., Tregear, S. J., Reston, J. T., & Turkelson, C. M. (2006). A system for rating the stability and strength of medical evidence. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(1), 1–20.

- Tricco, A. C., Tetzlaff, J., & Moher, D. (2011). The art and science of knowledge synthesis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(1), 11–20.

- Tsertsvadze, A., Chen, Y. F., Moher, D., Sutcliffe, P., & McCarthy, N. (2015). How to conduct systematic reviews more expeditiously? Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1–6.

- Vlayen, J., Aertgeerts, B., Hannes, K., Sermeus, W., & Ramaekers, D. (2005). A systematic review of appraisal tools for clinical practice guidelines: Multiple similarities and one common deficit. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 17(3), 235–242.

- Wright, R. W., Brand, R. R., & Spindler, K. P. (2007). How to write a systematic review. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 455, 23–29.

- Last Updated: